Study of Macro and Inflation (Part II)

Tilson’s viewpoint – Looking forward, as I’ve written many times, I continue to believe that a strong economy will keep overall inflation between 3% and 4%. This would keep the Fed on the sidelines, neither raising nor cutting rates. That means stock prices will be driven primarily by corporate earnings, which I expect will remain robust – hence, my constructive outlook for the markets.

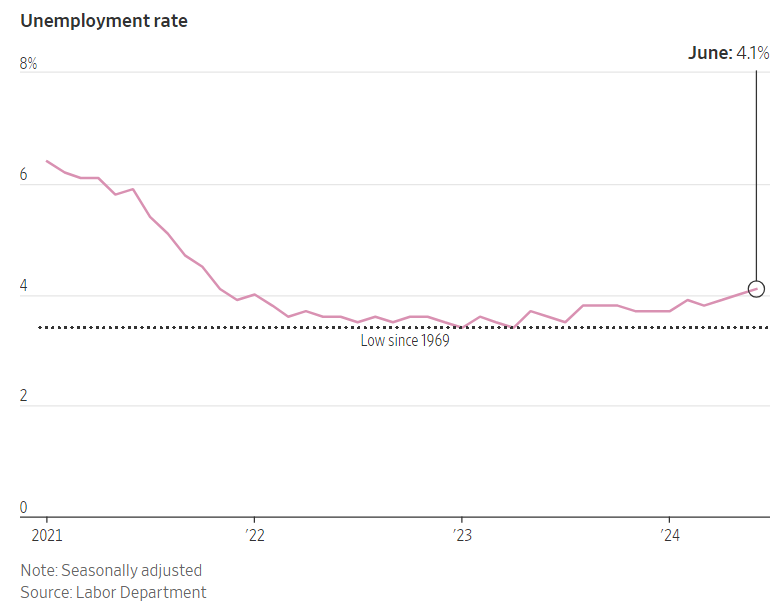

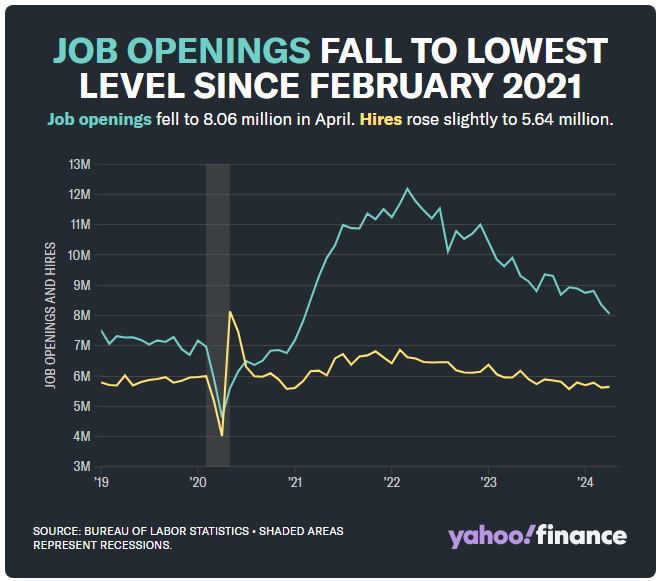

Unemployment, now at 3.9%, has held below 4% for more than two years, the longest such stretch in more than half a century. Unfilled job openings have declined significantly from a peak in early 2022, but remain well above prepandemic levels.

“All the hand-wringing about a slowdown in the labor market has been premature,” says Lara Rhame, chief U.S. economist at FS Investments. “People have a tendency to mistake normalization for weakness, when in fact the labor market remains quite strong.”

Time isn’t on the Fed’s side this year, however. Rate cuts at the Federal Open Market Committee’s June and July meetings are widely thought to be off the table, given the lack of progress on inflation so far in 2024. The September meeting will be “live,” meaning a decision could be made in the moment, but again, the data aren’t likely to cooperate, due to the economy’s enduring strength and technical factors.

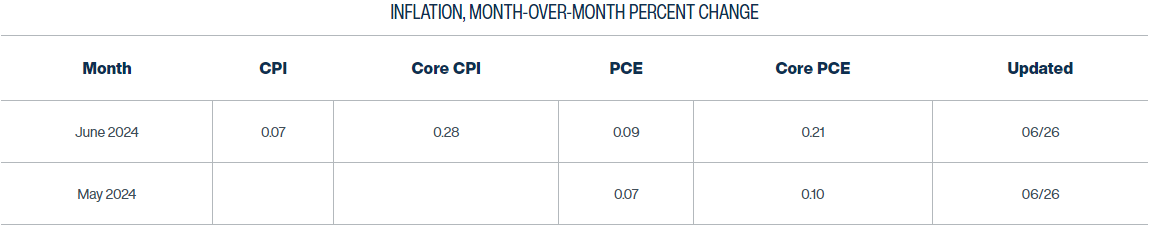

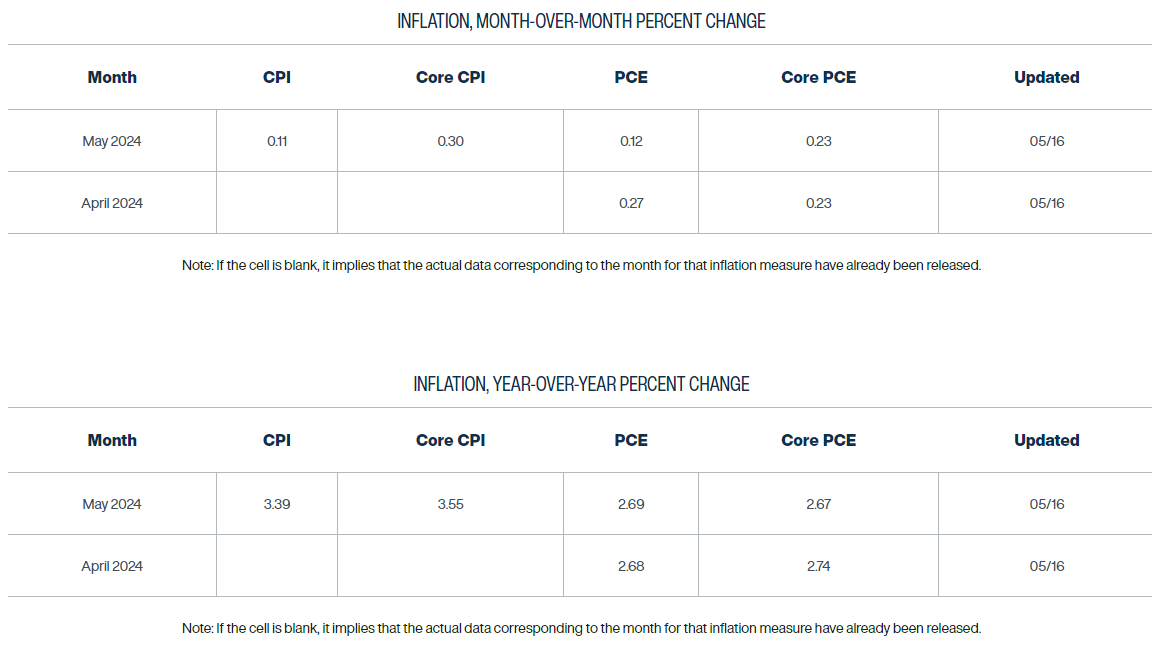

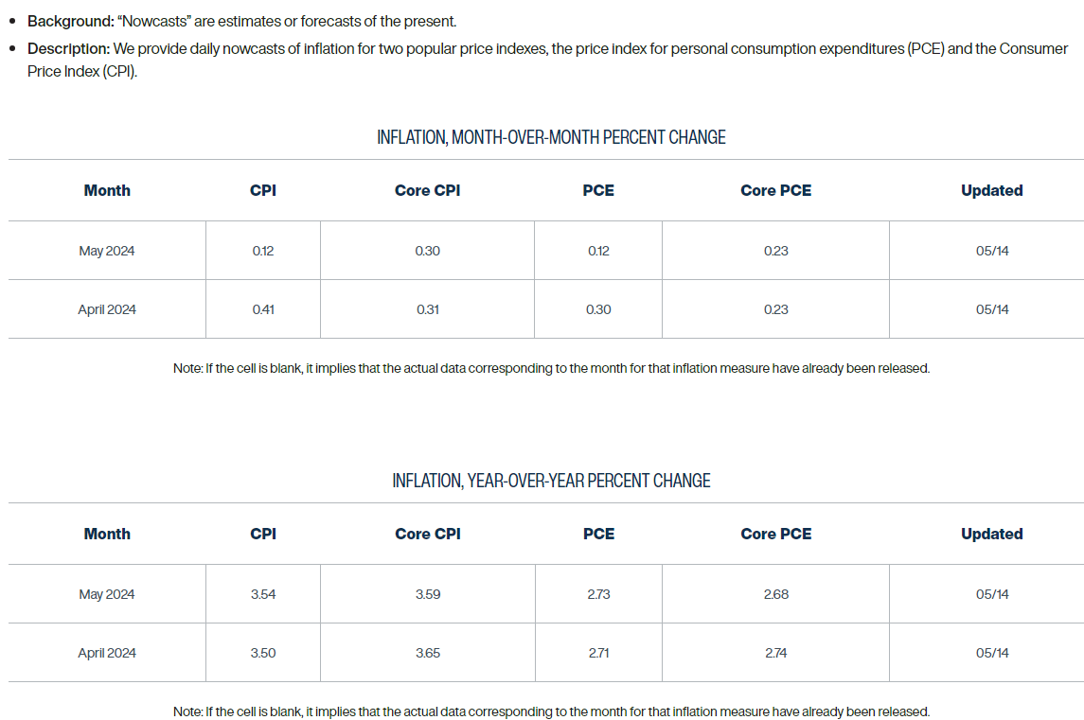

Base effects are one example. The PCE price index rose by 0.1% in May 2023, 0.2% in June of last year, and 0.1% in July. If inflation increases at a faster pace during the same months this year, the inflation rate will rise year over year, making it difficult for Fed officials to gain the confidence they desire that inflation is cooling toward 2%. The PCI price index hasn’t risen by less than 0.3% a month so far in 2024.

What about the November meeting? It will begin on Nov. 6, the day after Election Day, and unless the data scream for a change in interest rates, FOMC members probably won’t want to make waves, given the timing.

That leaves December as the last opportunity for a rate cut in 2024, but there are strong arguments for the status quo to hold.

For one, tighter monetary policy has been offset in the past two years by looser fiscal policy, and there is little reason to expect diminished federal largess in an election year—or in 2025, either. “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program,” as economist Milton Friedman famously said.

The U.S. federal budget deficit is on track to hit $1.5 trillion in the current fiscal year that ends on Sept. 30, equivalent to about 6% of U.S. GDP. That’s a powerful boost to growth that will continue to flow into the economy through the end of the year.

Monetary policy, meanwhile, might have a less powerful impact on the real economy than in past interest-rate cycles, partly because of the legacy of ultralow rates that prevailed from 2009 to 2022. As a result of that period, millions of homeowners are sitting with 30-year mortgages fixed at rates below 4%. Corporations likewise took the opportunity to refinance at historically low rates and extended their borrowings, while many of the largest U.S. companies are net interest earners.

Still, monthly data on jobs, inflation, and economic activity will move the market in the months ahead, and could inject more volatility. Election uncertainty will become more front of mind as November approaches and could be another source of turbulence. But absent a data shock that materially changes the Fed’s calculus, the stock market probably will sail through the noise.

“Nominal growth is still really good,” Rhame says. “And if you have the growth, you don’t need rate cuts for markets to continue to move higher.”

Economists immediately predicted the BoC would cut again in July.

The European Central Bank is most likely to follow suit on Thursday, financial markets foresee.

- 07/05/2024 – Case for September Rate Cut Builds After Slower Jobs Data – WSJ, Jobs report shows the unemployment rate ticked up to 4.1%, indicating slack in what has been a strong labor market

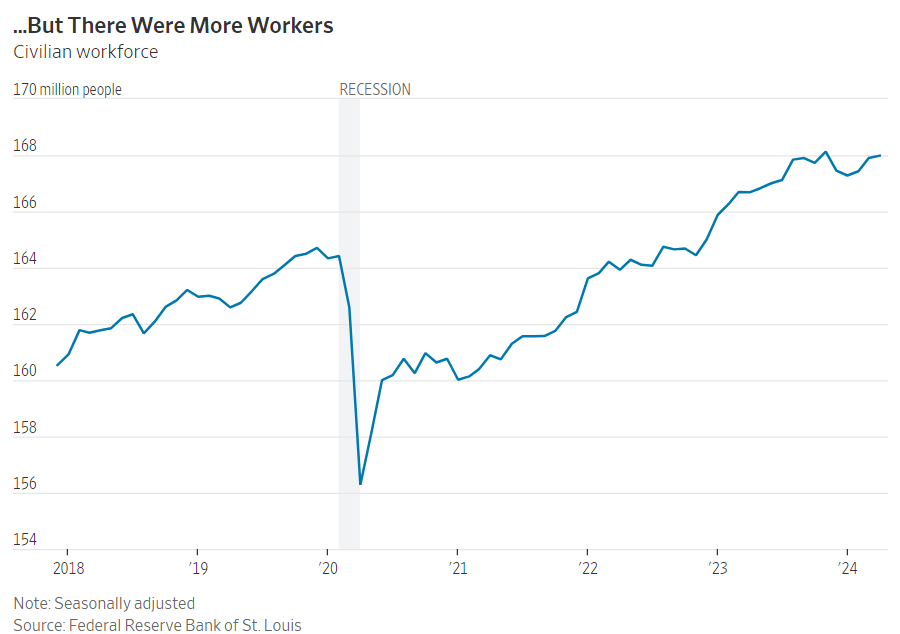

The Labor Department reported on Friday that the U.S. added a solid 206,000 jobs last month, slightly beating expectations and continuing a remarkably strong run. But the unemployment rate ticked up to 4.1%, a sign of slack in a labor market that has already shown some hints of gradually slowing down.

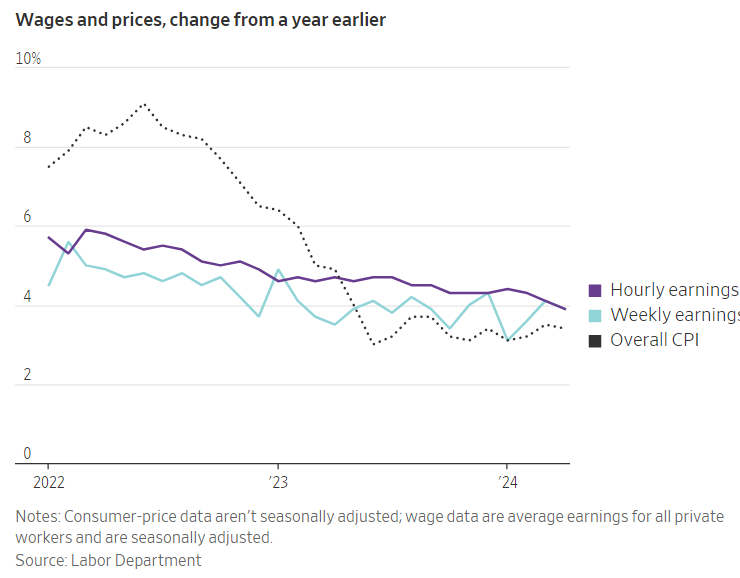

There were other indications as well that the job market is continuing to cool. Average hourly earnings were up 3.9% in June from a year earlier, marking their smallest gain since 2021. The counts for both April and May were revised lower by a combined 111,000 jobs. The labor force participation rate, the share of working-age people who were employed or seeking work, ticked up to 62.6%—an indication that more people entered the labor market.

The jobs report seems to have affirmed investors’ view that the economy is slowing, but not in a drastic way that would prompt more aggressive rate cuts. For President Biden’s re-election campaign, the continued job growth counts as a positive, but the rise in the unemployment rate robs it of a valuable talking point. The June report marked the first time since 2021 that the unemployment rate clocked in above 4%.

There likely wasn’t anything alarming enough in Friday’s payroll report to lead Fed officials to push for a July rate cut. But eventually, some Fed officials will say that the risks of a further weakening in the labor market aren’t desirable, even as others may argue that inflation still isn’t showing enough progress to cut rates.

While July may be too early for a rate cut, a mild inflation report next week could lead to Fed doves who are more worried about labor-market weakness to argue that it is time for the central bank to tee up a September rate cut.

One risk is that experience has shown the labor market can go from strong to weak in short order. While the unemployment rate of 4.1% is still historically low, it is up from 3.4% early last year.

The Sahm rule, a rule of thumb popularized by economist Claudia Sahm, says that if the average of the unemployment rate over three months rises a half-percentage point or more above the lowest the three-month average went over the previous year, the economy is in a recession. Over the past three months, the unemployment rate has averaged 4%—0.4 percentage point above the three-month average low of 3.6% over the past year.

High interest rates take time to fully work their way into the economy, but lately they have more clearly damped activity. Even though wages have been rising faster than prices, growth in consumer spending has slowed. “Signs of strain continue to emerge among consumers with low-to-moderate incomes, as their liquid savings and access to credit have increasingly become exhausted,” Fed governor Lisa Cook said in a speech last month.

If consumers cut back too much, employers could respond by cutting staff, turning what has been a virtuous cycle of rising employment and rising spending into a vicious one.

Job growth over the past year has been driven by three sectors: Healthcare, government, and leisure and hospitality. Together, they have accounted for 1.7 million of the 2.7 million jobs the economy has added over the past year. Much of that outsize growth is a matter of catching up, since all three sectors were much slower to get back to their prepandemic job levels than other employers.

Employment in all three sectors still appears low relative to their prepandemic job-growth trends. But it is unclear at what level demand for workers will be satiated, and once it is, overall job growth could slow markedly.

Hatzius thinks the best thing to do is watch the unemployment rate, which measures the share of people working or seeking work who are unemployed. If it keeps turning higher in the months ahead, it will be an indication that the labor market has moved from a point of balance to one of deterioration.

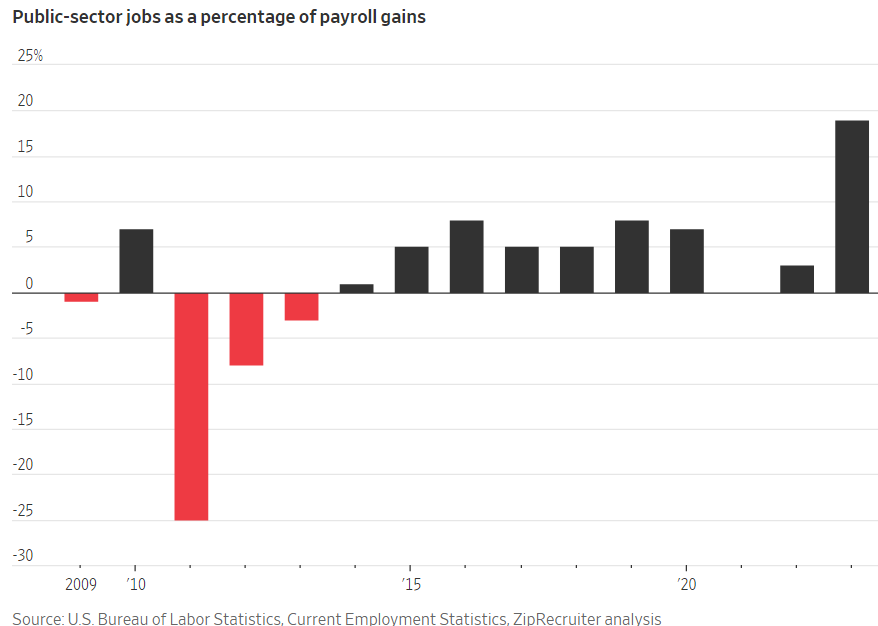

The Big Employer Still Adding Jobs and Boosting Pay: The Government – WSJ As many companies slow hiring, the public sector is adding workers

While many companies have been cutting staff and freezing new hires this year, the government is laying out the welcome mat.

Public-sector jobs at the federal, state and local level have risen by 327,000 positions so far in 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is approaching one-fifth of all new American jobs created in the first eight months of the year. In contrast, public-sector jobs accounted for 5% of employment growth during the equivalent period last year.

“After two years of very underwhelming government hiring, it’s a necessary catch-up,” said Julia Pollak, an economist at online jobs site ZipRecruiter.

Much of the recent hiring spree has been to backfill jobs left open by millions of teachers, police officers and other public servants who quit during the pandemic. Other roles at government agencies languished because the public sector couldn’t effectively compete against private employers that were offering pay raises and signing bonuses to attract talent during several years of a white-hot labor market.

But just as layoffs hit sectors from tech to finance, government agencies have boosted funding for new hires and have dangled richer perks. This year’s growth in public-sector jobs represents the highest share of overall U.S. payroll gains since 2001, when the government hired masses of workers focused on public safety after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Pollak said.

Minutes of the Federal Reserve’s June meeting show officials are not in any agreement over how many months of good inflation data might be needed before the central bank might be confident enough that low inflation was here to stay before cutting interest rates.

Officials “noted that the uncertainty associated with the economic outlook and with how long it would be appropriate to maintain a restrictive policy stance,” the minutes said.

FOMC Minutes June 11–12, 2024 (federalreserve.gov)

- 07/02/2024 – Fed’s Jerome Powell Turns Dial Toward Interest-Rate Cut Later This Year – WSJ The central bank is trying to pull off a soft landing in which inflation slows without a serious downturn

Officials will have three more months of data on hiring, inflation and spending before then, making it difficult to firmly stake out a view right now on what may be a finely balanced decision. Powell declined to say whether he was setting the table for a September cut. “I’m not going to be landing on any specific dates here today,” he said.

Investors in interest-rate futures markets see a roughly 70% chance that the first Fed cut occurs by September, according to CME Group. U.S. stock indexes rose Tuesday, with the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite hitting records.

To determine whether and when to lower interest rates, officials must balance two risks. The first is that a continuing cooling in the labor market accelerates in a way that is hard to stop once it starts. The second is that lower rates ignite economic activity and allow inflation to settle out above their goal.

- 07/02/2024 – Fed Chair Jerome Powell: US inflation is cooling again, though it isn’t yet time to cut rates (msn.com)

Speaking in a panel discussion at the European Central Bank’s monetary policy conference in Sintra, Portugal, Powell said Fed officials still want to see annual price growth slow further toward their 2% target before they would feel confident of having fully defeated high inflation.

“We just want to understand that the levels that we’re seeing are a true reading of underlying inflation,” he added.

Powell also acknowledged that the Fed is treading a fine line as it weighs when to cut its benchmark interest rate, which it raised 11 times from March 2022 through July 2023 to its current level of 5.3%. The rate hikes were intended to curb the worst streak of inflation in four decades by slowing borrowing and spending by consumers and businesses. Inflation did tumble from its peak in 2022 yet still remains elevated.

In Full: Goolsbee on Fed Policy, Inflation, Labor, Rates | Watch (msn.com)

Traders are preparing for the release of the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price index data, widely regarded as the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure, scheduled for Friday.

May’s PCE Price Index Report: What Economists Expect

- The PCE price index is expected to slow from 2.7% year-on-year in April to 2.6% year-on-year in May, as estimates gathered by Econoday show. The consensus range is between 2.5% and 2.7%.

- On a monthly basis, the PCE price index is seen advancing at a 0.1% pace, slowing down from the previous 0.3%.

- The core PCE price index is set to ease from 2.8% to 2.6% year-on-year in May, which could mark the lowest level since March 2021.

- On a monthly basis, the core PCE price index is predicted to slow from 0.2% to 0.1%.

Inflation Nowcasting (clevelandfed.org)

06/17/2024 – Rent Hikes Loom, Posing Threat to Inflation Fight – WSJ

- 06/16/2024 – How to be a Profitable Trader in 2024 (make the year COUNT) (youtube.com)

- 06/12/2024 – Fed Projects Just One Cut This Year Despite Mild Inflation Report – WSJ Central bankers see inflation returning closer to their goal next year after longer wait on reductions

Federal Reserve officials penciled in just one interest-rate cut for this year, indicating most are in no hurry to lower rates, even after a widely watched report Wednesday showed inflation improved last month.

New economic projections showed 15 of 19 officials expect the Fed to cut rates this year, with that group roughly split between one or two rate cuts. The median, or midpoint, of those projections reflected expectations of one rate cut.

Fed officials meet four more times this year, in July, September, November and December, and the rate projections could temper expectations of a September cut that investors anticipated earlier Wednesday after the inflation report.

- 06/12/2024 -The heaviest concentration in history

- 06/06/2024 – European Central Bank Cuts Interest Rates for First Time Since 2019 – WSJ A scenario where the ECB cuts rates further while the Fed stays put would risk reducing the euro’s strength against the dollar, pushing up the cost of imports and lifting eurozone inflation higher. This could delay further loosening in Europe, whose economy is in bigger need of relief than the robustly growing U.S. economy.

The ECB said it would reduce its key interest rate to 3.75% from 4%, its first rate cut in almost five years. Future interest-rate decisions will be based on incoming economic data, the bank said in a statement. The ECB’s rate-setting committee “is not pre-committing to a particular rate path,” the bank said.

The rate cut is a significant moment for investors and the world economy. It marks an inflection point in recent monetary policy and sends a signal that relief is on the way for households, indebted governments and businesses that have reined in investments in the face of high borrowing costs.

The cut also potentially puts the ECB and the Fed on different tracks and widens an existing gap in borrowing costs between the U.S. and Europe. While this could boost Europe’s growth in the short term, the gap could also complicate the work of policymakers, especially in Europe.

The Bank of Canada on Wednesday trimmed its key policy rate by 25 basis points to 4.75%, in a widely expected move that marked its first cut in four years, and said more easing was likely if inflation continued to ease.

Bank of Canada Cuts Rates to Become First G-7 Central Bank to Ease Policy – WSJ Gov. Tiff Macklem signals more cuts are possible as inflation cools

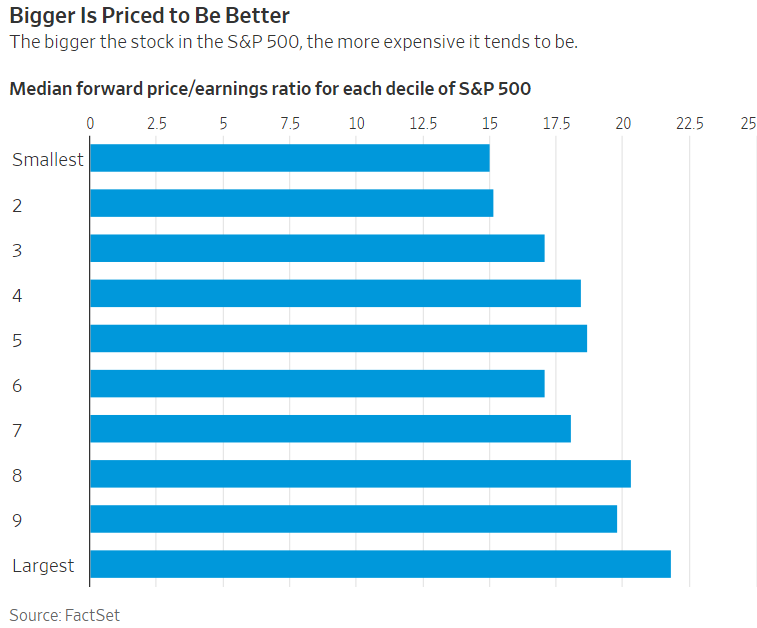

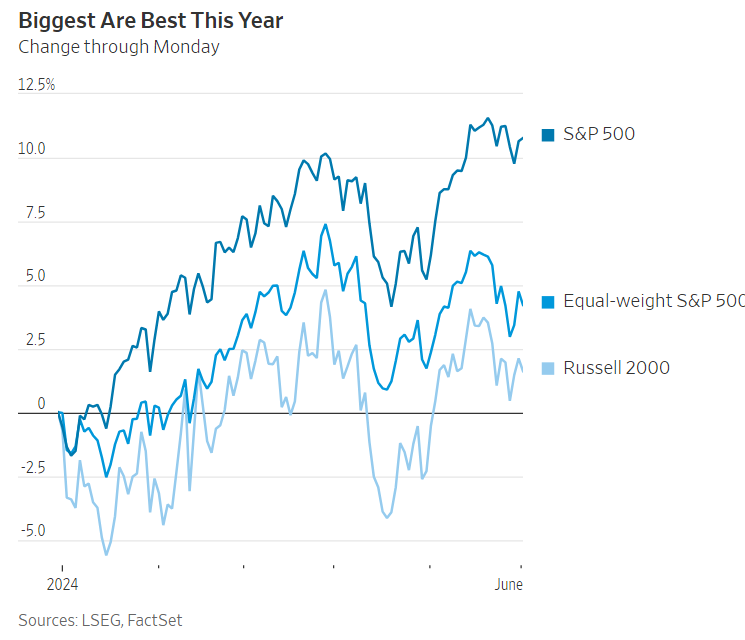

- 06/05/2024 – Big Tech Companies Unplug Stock Market From Reality – WSJ The big-vs.-small-stocks phenomenon reflects the same disconnects we see in the broader economy. If rate cuts do come to pass, the little guys should finally get the chance to put Big Tech in the shade. lowly valued companies were regarded as less reliant on future profits that are worth less in a world of higher rates. The Big Tech stocks that dominate the market sit on huge cash piles, while the biggest companies chose to lock in low interest rates for a long time by refinancing their bonds before the Fed began raising rates in 2022. Smaller companies tend not to have cash piles on which to earn fat savings interest and have more need to issue bonds to raise cash. The smallest don’t even have access to the bond market, one reason the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies has lagged so far behind the S&P this year, eking out a gain of just 1.6%.

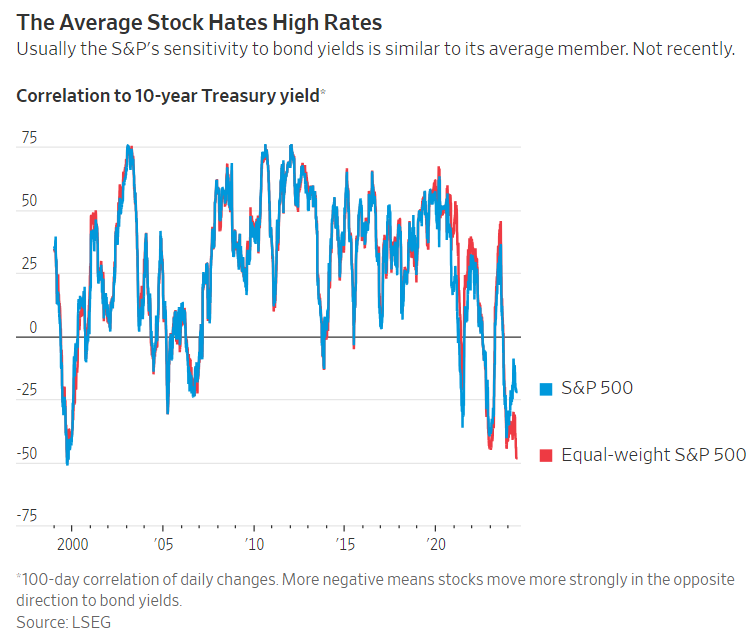

Big Tech stocks aren’t just dominating the market. They’re also hiding just how scared investors are that the Federal Reserve will keep rates higher for longer.

The average stock in the S&P 500 is hurt more by rising yields—and helped more by falling yields—than any time this century. Yet the S&P itself is far less affected by the outlook for interest rates, because the Big Tech stocks that make up so much of the standard, value-weighted index are insulated from the Fed by their enormous cash piles.

Aside from AI, I think this is best explained by corporate profits and interest rates, and to a lesser extent concern about the economy.

The Big Tech stocks that dominate the market sit on huge cash piles, while the biggest companies chose to lock in low interest rates for a long time by refinancing their bonds before the Fed began raising rates in 2022. Smaller companies tend not to have cash piles on which to earn fat savings interest and have more need to issue bonds to raise cash. The smallest don’t even have access to the bond market, one reason the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies has lagged so far behind the S&P this year, eking out a gain of just 1.6%.

The oddity about the market’s reaction this year is that it is almost exactly the opposite of what happened in 2022. Then, Big Tech stocks plunged as investors marked down their heady valuations, dragging the S&P down 19% over the year. Meanwhile the average stock was down just 13%, as smaller, lowly valued companies were regarded as less reliant on future profits that are worth less in a world of higher rates.

Why the difference? The AI excitement offsets the valuation hit. The rate shock this year—from expecting six Fed cuts to just one or two—is a different scale to 2022, when rates soared from zero to 4.5%. And investors have woken up to the long-dated debt and cash hoards that shield so many of the biggest stocks.

Investors outside the Big Tech sector are right to worry about higher rates. For those looking for bargains, the high valuation of the S&P hides the fact that its smallest 50 members are almost as cheap, at a median 15 times forward earnings, as the index as a whole was at the nadir of the Covid-19 panic in 2020.

If rate cuts do come to pass, the little guys should finally get the chance to put Big Tech in the shade.

Job openings fell in April to their lowest level since February 2021 as the labor market shows further signs of cooling off from the hiring boom that followed the US economy reopening after the pandemic.

New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics released Tuesday showed there were 8.06 million jobs open at the end of April, a decrease from the 8.35 million job openings in March.

- 06/01/2024 – Eurozone Inflation Rises as ECB Considers Rate-Cut Path (msn.com)

- 06/01/2024 – The Fed Won’t Cut Rates This Year (msn.com)

The Federal Reserve isn’t likely to lower interest rates in 2024. Elevated inflation, a resilient economy, and a still-strong, if softening labor market argue against the need for easing monetary policy, especially as these conditions are expected to persist through year end.

- 05/27/2024 – ECB ready to start cutting interest rates, chief economist says (msn.com) The European Central Bank will likely cut interest rates from historic highs at its meeting on June 6th. If the ECB diverges from the Fed by cutting interest rates more quickly it could cause the euro to fall and push up inflation by raising import prices, but Lane said the ECB would take any “significant” exchange rate move into account. He noted that “there has been very little movement” in this direction so far. The euro has risen recently against the U.S. dollar from a six-month low in April.

“Barring major surprises, at this point in time there is enough in what we see to remove the top level of restriction.” — Philip Lane, ECB chief economist

The European Central Bank will likely cut interest rates from historic highs at its meeting on June 6th, suggested its chief economist, Philip Lane, in an interview with the Financial Times on Monday. And he brushed off fears that doing so before the U.S. Federal Reserve could backfire.

Investors are betting that the ECB will lower its benchmark deposit rate by a quarter percentage point from its record high of 4% at next week’s meeting after eurozone inflation fell close to the bank’s 2% target.

He said the pace at which the central bank lowered eurozone borrowing costs this year would be decided by assessing data to decide “is it proportional, is it safe, within the restrictive zone, to move down”.

“Things will be bumpy and things will be gradual,” said Lane, who will draft the proposed rate decision before it is decided by the 26 members of the governing council next week.

If the ECB diverges from the Fed by cutting interest rates more quickly it could cause the euro to fall and push up inflation by raising import prices, but Lane said the ECB would take any “significant” exchange rate move into account. He noted that “there has been very little movement” in this direction so far. The euro has risen recently against the U.S. dollar from a six-month low in April.

- 05/22/2025 – Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, April 30–May 1, 2024 (federalreserve.gov) overall, negative viewpoint on the disinflation process. Even though this minute was before the release of May 15 (good inflation) report – not good for KRE and XBI which are sensitive to the interest rate

- The manager turned first to a review of developments in financial markets. Domestic data releases over the inter-meeting period pointed to inflation being more persis-tent than previously expected and to a generally resilient economy. Policy expectations shifted materially in re-sponse. The policy rate path derived from futures prices implied fewer than two 25 basis point rate cuts by year-end. The modal path based on options prices was quite flat, suggesting at most one such rate cut in 2024. The median of the modal paths of the federal funds rate ob-tained from the Open Market Desk’s Survey of Primary Dealers and Survey of Market Participants also indicated fewer cuts this year than previously thought. Respond-ents’ baseline expectations for the timing of the first rate cut—which had been concentrated around June in the March surveys—shifted out significantly and became more diffuse.

- Although credit quality for household loans remained solid, on balance, delinquency rates for credit cards and auto loans in the fourth quarter remained notably above their levels just before the pandemic. For residential mortgages, delinquency rates across loan

- the share of nonperforming CRE loans at banks—defined as loans past due 90 days or in nonac-crual status—rose further through March, especially for loans secured by office buildings

- the fair value of bank assets was estimated to have fallen further in the first quarter, re-flecting the substantial duration risk on bank balance sheets.

- The economy was expected to maintain its high rate of resource utilization over the next few years, with pro-jected output growth roughly similar to the staff’s esti-mate of potential growth. The unemployment rate was expected to edge down slightly over 2024 as labor mar-ket functioning improved further, and to remain roughly steady thereafter.

- The risks around the forecast for economic activity were seen as skewed to the down-side on the grounds that more-persistent inflation could result in tighter financial conditions than in the staff’s baseline projection; in addition, deteriorating household financial positions, especially for lower-income house-holds, might prove to be a larger drag on activity than the staff anticipated.

- housing services inflation had slowed less than had been anticipated based on the smaller increases in measures of market rents over the past year. A few participants remarked that unusually large seasonal patterns could have contributed to Janu-ary’s large increase in PCE inflation, and several partici-pants noted that some components that typically display volatile price changes had boosted recent readings. However, some participants emphasized that the recent increases in inflation had been relatively broad based and therefore should not be overly discounted.

- Participants noted that they continued to expect that in-flation would return to 2 percent over the medium term. However, recent data had not increased their confidence in progress toward 2 percent and, accordingly, had sug-gested that the disinflation process would likely take longer than previously thought.

- Participants discussed several factors that, in conjunction with appropriately re-strictive monetary policy, could support the return of in-flation to the Committee’s goal over time. One was a further reduction in housing services price inflation as lower readings for rent growth on new leases continued to pass through to this category of inflation. However, many participants commented that the pass-through would likely take place only gradually or noted that a re-acceleration of market rents could reduce the effect.

- Several participants stated that core nonhousing services price inflation could resume its decline as wage growth slows further with labor demand and supply moving into better balance, aided by higher labor force participation and strong immigration flows. In addition, many partic-ipants commented that ongoing increases in productivity growth would support disinflation if sustained, though the outlook for productivity growth was regarded as un-certain.

- Participants assessed that demand and supply in the la-bor market, on net, were continuing to come into better balance, though at a slower rate.

- Participants discussed a range of risks emanating from the banking sector, including unrealized losses on assets resulting from the rise in longer-term yields, high CRE exposure, significant reliance by some banks on uninsured depos-its, cyber threats, or increased financial interconnections among banks. Several participants commented on the rapid growth of private credit markets, noting that such developments should be monitored because the sector was becoming more interconnected with other parts of the financial system and that some associated risks may not yet be apparent.

- Participants generally noted that high interest rates could contribute to vulnerabilities in the financial system.

- Although monetary policy was seen as restrictive, many partici-pants commented on their uncertainty about the degree of restrictiveness. These participants saw this uncer-tainty as coming from the possibility that high interest rates may be having smaller effects than in the past, that longer-run equilibrium interest rates may be higher than previously thought, or that the level of potential output may be lower than estimated. Participants assessed, however, that monetary policy remained well positioned to respond to evolving economic conditions and risks to the outlook. Participants discussed maintaining the cur-rent restrictive policy stance for longer should inflation not show signs of moving sustainably toward 2 percent or reducing policy restraint in the event of an unexpected weakening in labor market conditions. Various partici-pants mentioned a willingness to tighten policy further should risks to inflation materialize in a way that such an action became appropriate.

- 05/22/2024 – Data did not increase Fed’s confidence that inflation is heading toward 2%: FOMC minutes | Seeking Alpha

After the Federal Reserve’s March policy meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the policymakers were looking for more evidence that the economy was making progress in reaching the central bank’s inflation goal. They didn’t get that confidence at their most recent meeting.

At its April 30-May 1 meeting, “recent data had not increased their confidence in progress toward 2%, and, accordingly, had suggested that the disinflation process would likely take longer than previously thought,” according to the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s last meeting on April 30-May 1.

The Federal Reserve kept its policy rate unchanged at 5.25%-5.50% at its last meeting, citing a lack of further progress toward its 2% inflation goal in recent months.

The FOMC members also discussed the degree to which the Fed’s policy is restrictive. And there seemed to be some uncertainty on this point. ” Although monetary policy was seen as restrictive, many participants commented on their uncertainty about the degree of restrictiveness,” the minutes said.

Those questioning the amount of restrictiveness said there could be a few factors making it hard to assess. High interest rates may be having smaller effects than in the past, longer-run equilibrium interest rates may be higher than previously thought, or the level of potential output may be lower than estimated, they said.

With that said, the officials consider the Fed’s policy stance to be well-positioned. They can ease policy in the event of unexpected weakening in labor market conditions. On the other side, “various participants mentioned a willingness to tighten policy further should risks to inflation materialize in a way that such an action became appropriate,” the minutes said.

- 05/16/2024 – Inflation Nowcasting (clevelandfed.org)

U.S. consumer prices increased less than expected in April, suggesting that inflation resumed its downward trend at the start of the second quarter in a boost to financial market expectations for a September interest rate cut.

Hopes of the Federal Reserve starting its easing cycle this year were further bolstered by other data on Wednesday showing retail sales were unexpectedly flat last month. The reports suggested that domestic demand was cooling, which will be welcomed by officials at the U.S. central bank as they try to engineer a “soft-landing” for the economy.

The cost of shelter, which includes rents, increased 0.4% for the third straight month. Gasoline prices shot up 2.8%. These two categories contributed over 70% of the increase in the CPI. Food prices were unchanged. Prices at the supermarket fell 0.2%, with eggs dropping 7.3%. Meat, fish, fruits and vegetables as well as nonalcoholic beverages were also cheaper.

RENTS STICKY

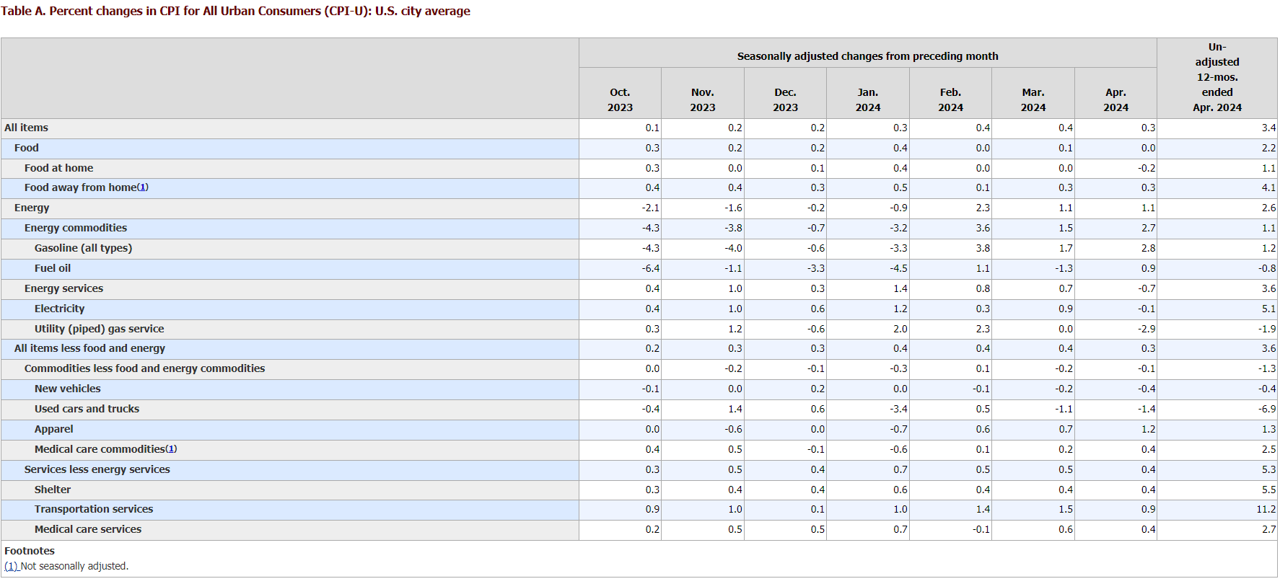

Excluding the volatile food and energy components, the CPI rose 0.3% in April after advancing 0.4% for three straight months. That lowered the three-month annualized increase in the so-called core CPI to a 4.1% rate from a 4.5% rate.

Rents increased 0.4%. Owners’ equivalent rent (OER), a measure of the amount homeowners would pay to rent or would earn from renting their property, also gained 0.4% after a similar rise in March and February. Market rents have been trending lower and that is expected to show in the CPI data this year.

Based on the CPI and PPI data, economists estimated that the core personal consumption expenditures price index rose 0.2% in April after gaining 0.3% in March. That would lower the annual increase in core inflation to 2.7% from 2.8% in March.

- 05/15/2024 – Money Life with Chuck Jaffe: Whitney Tilson on letting winners run as market hits new highs (libsyn.com) 16:53 ~ 35:50

- large companies have good balance sheet and less debt, better than those of mid and small companies. Therefore, they thrive in the high rate environment

- I am looking for opportunities in mid and small companies

- market is at all time high, but I do not see signs of danger here, not like those of 1999 internet bubble and 2008 housing bubble

- Us economy is the best in the world, better than EU and China

- be very cautious about investment in Chinese companies, China government policy does not work well by aliening with western world but align with Russia

- learn to tune out the noises from market news

- 05/15/2024 – Eurozone Inflation Set to Ease More Rapidly, EU Says – WSJ The 20-member euro area should book average inflation of 2.5% for 2024 and 2.1% in 2025, the European Commission says

The eurozone’s annual rate of inflation is set to fall faster than previously expected as economic growth remains anemic, and hit the European Central Bank’s target earlier in 2025, the European Union forecast.

The 20-member euro area should book average inflation of 2.5% for 2024 and 2.1% in 2025, the European Commission said Wednesday, lower than previous projections set out in February. The new forecasts will likely reassure policymakers at the ECB, who have signaled they are likely to lower their key interest rate when they meet on June 6.

“Starting from a lower-than-expected turnout in the first months of this year, inflation is forecast to continue declining and reach target slightly earlier in 2025 than projected in the Winter interim forecast,” the Commission said.

Eurozone inflation has fallen steadily over recent months, in contrast to the U.S., where recent readings have been hotter than anticipated. While the eurozone economy has largely flatlined since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, the U.S. economy has grown rapidly.

The EU expects the growth gap to narrow over coming years, but only slightly. Indeed, it lowered its growth forecasts for the eurozone in 2025, to 1.4% from 1.5%.

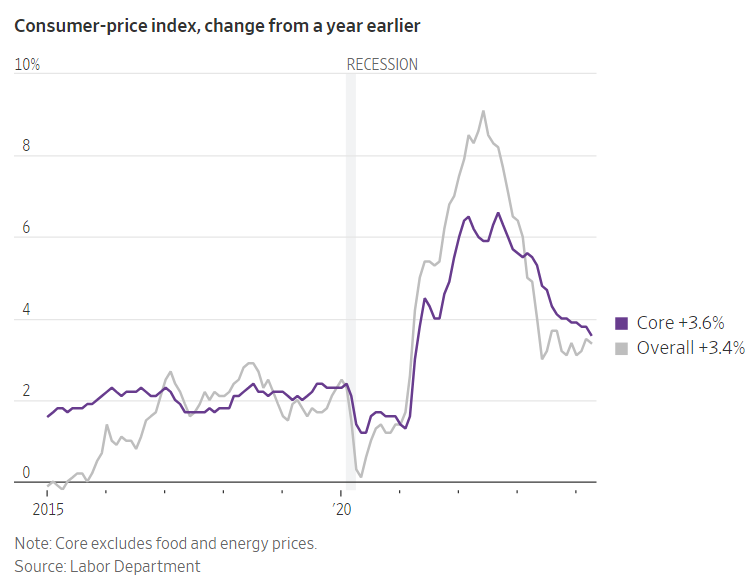

U.S. inflation eased slightly in April, with a key measure of price pressures slowing to its lowest level since spring 2021.

The consumer-price index, a gauge for goods and service costs across the U.S. economy, rose 3.4% in April from a year ago, the Labor Department said Wednesday. So-called core prices that exclude volatile food and energy items climbed 3.6% annually, the lowest increase since April 2021. Both figures were in line with economists’ expectations.

Investors saw positive signs in the report that the Federal Reserve’s inflation fight is gradually slowing down the U.S. economy. The yields on 10-year Treasurys, which fall as prices rise, ticked lower. Stocks advanced, continuing their march higher in May.

Because it will likely take another two reports to shore up officials’ confidence that inflation can return to the lower levels that prevailed before the pandemic, the Fed might not be ready to cut interest rates before September.

U.S. consumer sentiment veered sharply lower in May, according to preliminary results of a University of Michigan survey released last week. Americans’ outlook darkened in part due to expectations that both inflation and interest rates will stay elevated, pressuring households’ day-to-day budgets and keeping mortgage rates high.

- 05/14/2024 – Inflation Nowcasting (clevelandfed.org)

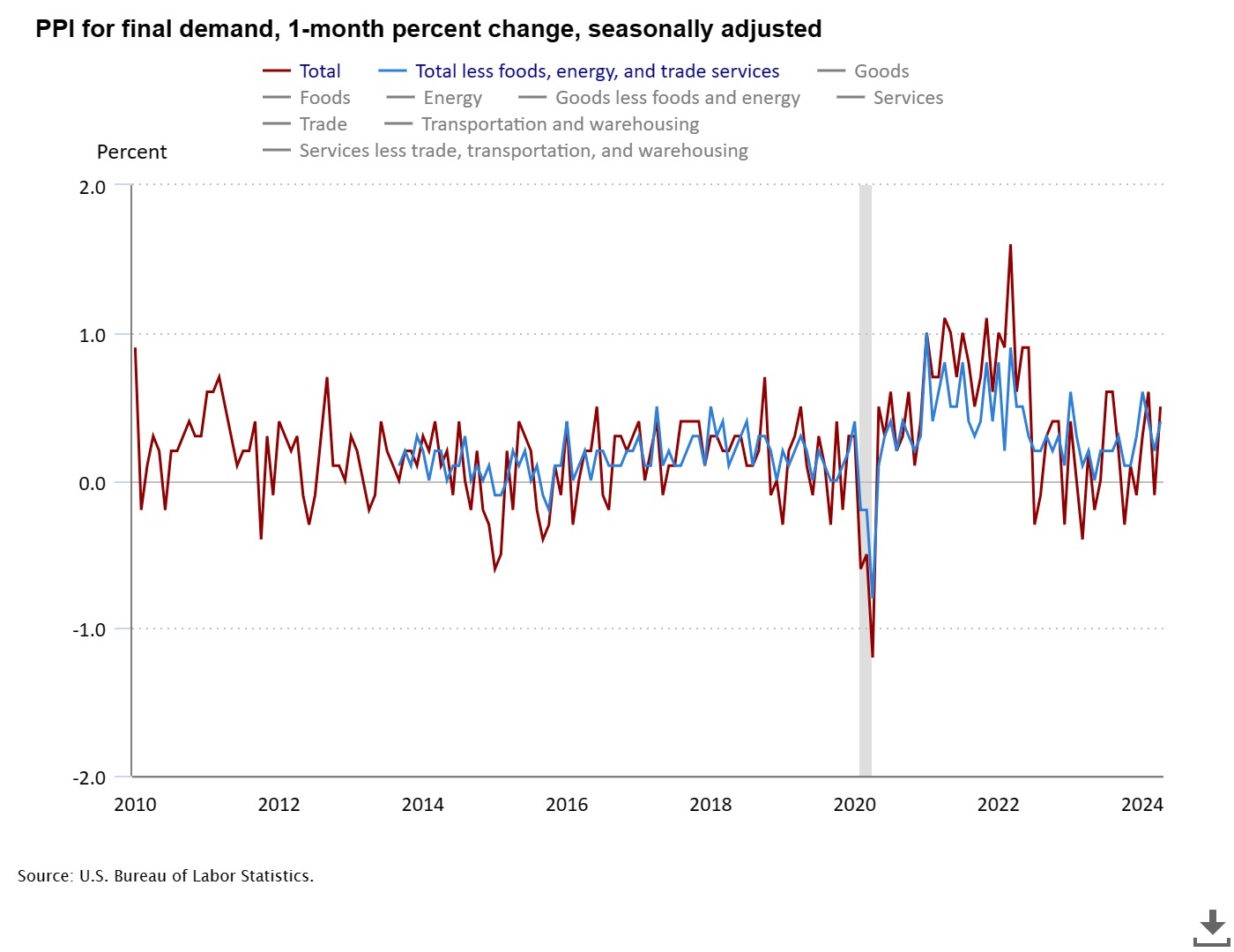

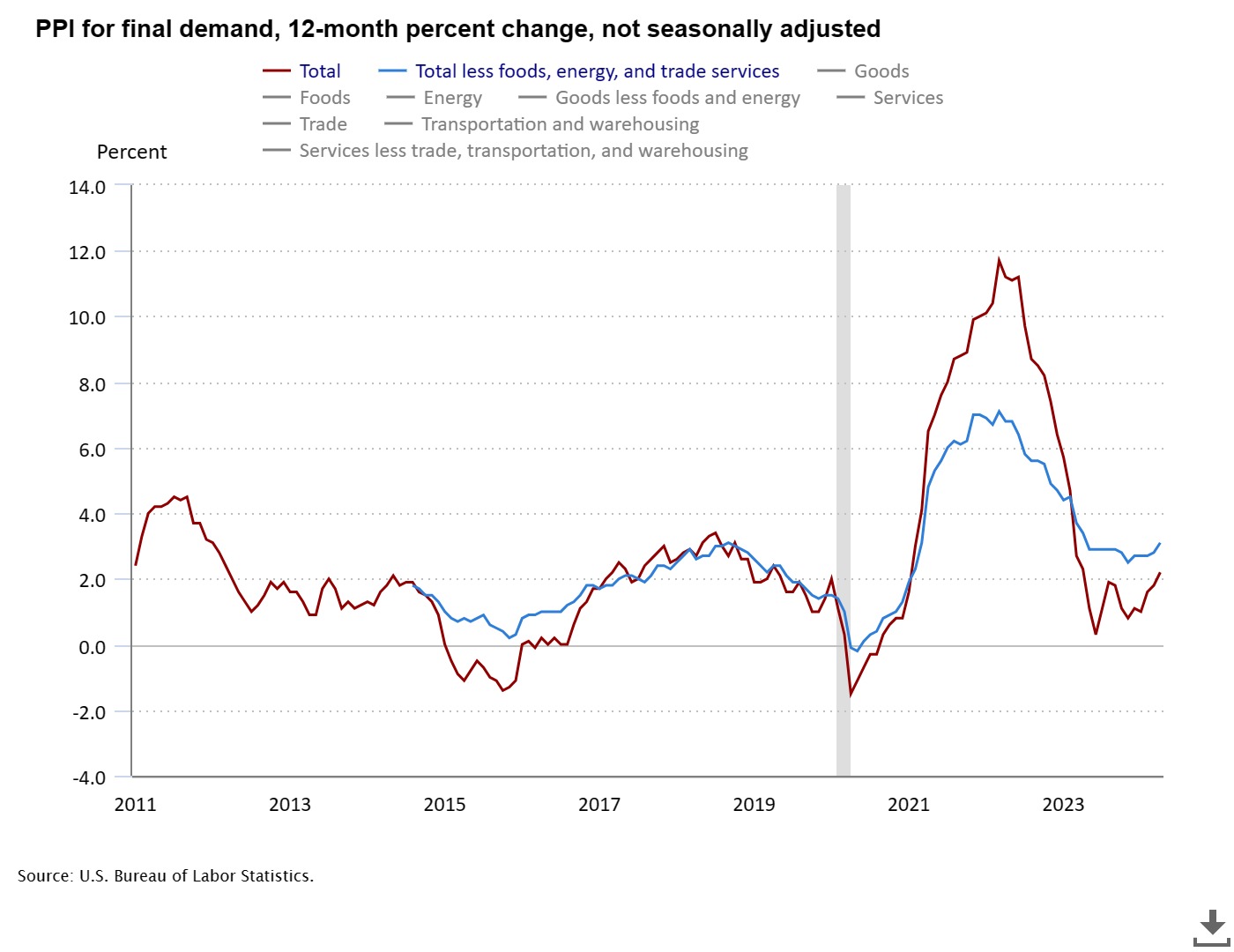

- 05/14/2024 – Producer Price Indexes for final demand, 1-month percent change, seasonally adjusted (bls.gov)

Producer Price Index News Release summary – 2024 M04 Results (bls.gov)

The Producer Price Index for final demand rose 0.5 percent in April, seasonally adjusted, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Final demand prices declined 0.1 percent in March and advanced 0.6 percent in February. (See table A.) On an unadjusted basis, the index for final demand moved up 2.2 percent for the 12 months ended in April, the largest increase since rising 2.3 percent for the 12 months ended April 2023.

Nearly three-quarters of the April advance in final demand prices is attributable to a 0.6-percent increase in the index for final demand services. Prices for final demand goods moved up 0.4 percent.

The index for final demand less foods, energy, and trade services moved up 0.4 percent in April after rising 0.2 percent in March. For the 12 months ended in April, prices for final demand less foods, energy, and trade services increased 3.1 percent, the largest advance since climbing 3.4 percent for the 12 months ended April 2023.

Final Demand

Final demand services: The index for final demand services moved up 0.6 percent in April, the largest rise since jumping 0.8 percent in July 2023. Seventy percent of the April increase can be traced to prices for final demand services less trade, transportation, and warehousing, which advanced 0.6 percent. Margins for final demand trade services rose 0.8 percent. (Trade indexes measure changes in margins received by wholesalers and retailers.) In contrast, prices for final demand transportation and warehousing services decreased 0.6 percent.

Product detail: A 3.9-percent advance in the index for portfolio management was a major factor in the April increase in prices for final demand services. The indexes for machinery and equipment wholesaling, residential real estate services (partial), automobiles retailing (partial), guestroom rental, and truck transportation of freight also moved higher. Conversely, prices for airline passenger services declined 3.8 percent. The indexes for fuels and lubricants retailing and for gaming receipts (partial) also fell. (See table 2.)

Final demand goods: Prices for final demand goods rose 0.4 percent in April after decreasing 0.2 percent in March. Most of the advance is attributable to the index for final demand energy, which moved up 2.0 percent. Prices for final demand goods less foods and energy increased 0.3 percent. In contrast, the index for final demand foods declined 0.7 percent.

Product detail: Nearly three-quarters of the April advance in the index for final demand goods can be traced to a 5.4-percent increase in gasoline prices. The indexes for diesel fuel; chicken eggs; electric power; nonferrous metals; and canned, cooked, smoked, or prepared poultry also rose. Conversely, prices for fresh and dry vegetables fell 18.7 percent. The indexes for residential natural gas and for steel mill products also declined.

- 05/11/2024 – Stubbornly High Rents Prevent Fed From Finishing Inflation Fight – WSJ For more than a year, the central bank has expected slowing rent increases to show up in official housing measures

Market rents—rents on newly signed leases—surged three years ago, reflecting the unusual demand for more space unleashed by the pandemic, strong income growth and historically low inventories of homes for rent or purchase. Single-family home rents rose 14% in 2022, according to CoreLogic.

But year-over-year rent growth slowed to 3.4% in February, reflecting increased competition from new apartment supply and tepid inflation-adjusted income growth. Apartment rents have notched similar declines, according to Zillow.

Because only a minority of leases turn over each year, changes in market rents are reflected in inflation with a lag. Accounting for that lag, Fed officials, Wall Street investors, and private-sector economists have expected housing inflation to slow since late 2022 based on what has already happened with market rents.

Housing inflation has indeed slowed from a peak of 8.2% one year ago—but only to 5.6% in March, “a much slower pace than pretty much anybody anticipated,” said Jay Parsons, head of residential strategy at Madera Residential, a Texas-based apartment owner. The Labor Department is scheduled to report April inflation on Wednesday.

Deconstructing inflation

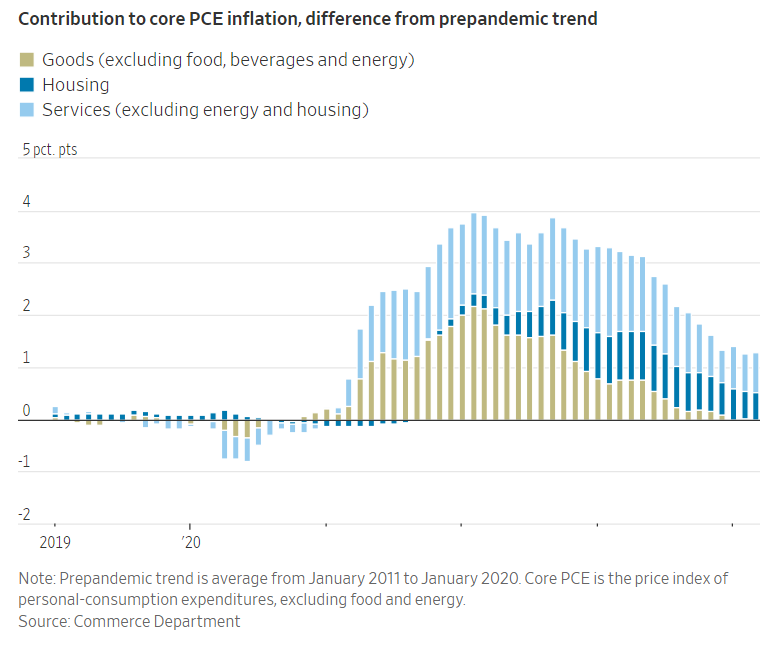

Housing helps explain why core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, has stalled in recent months, contrary to expectations of a continued cooling. Core PCE inflation was 2.8% in March, down from 5.6% in 2022 but not much lower than in December.

Housing “has not behaved the way we thought it would,” Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee said in an interview last month. “I still think it will, but if it doesn’t, we’re going to have a hard time” bringing inflation back to 2%.

To understand why, break core inflation into three different baskets: goods, housing and nonhousing services. To get all the way to 2% inflation, the Fed doesn’t need 2% for all those categories.

In the decade before the pandemic, core inflation was slightly below 2%, the result of inflation in goods running at about minus 1%, housing at 2.5% to 3.5%, and nonhousing services at slightly above 2%.

Much of last year’s slowdown in inflation was because goods prices returned to their prepandemic trend. For inflation to get back to 2%, nonhousing services inflation has to drop to less than 3% from 3.5% now, and housing to around 3.5% from 5.8%.

If inflation stays higher, Fed officials are likely to hold interest rates at their current levels, the highest in two decades, until they see more concrete evidence that the economy is slowing.

- 05/06/2024 – U.S. Jobs Growth Set to Slow, Conference Board Says – WSJ Conference Board’s employment trends index fell to 111.25 in April

U.S. jobs growth could stall in the second half of 2024, with signs of a slowing labor market, according to monthly gauge of employment trends

The Conference Board’s employment trends index fell to 111.25 in April from a downwardly revised 112.16 in March, the private-research group said Monday.

“The labor market is beginning to show signs of cooling following a period of very strong growth since the pandemic recession,” said Will Baltrus, associate economist at The Conference Board.

However, substantial job losses are unlikely to occur over the coming months, as employers are still facing labor shortages, Baltrus said.

The reading comes after Labor Department figures published last week that showed the U.S. added 175,000 more jobs in April, fewer than in March, with the unemployment rate ticking up to 3.9% from 3.8% in the prior month.

Labor: Jobs are far less plentiful than they were. While there are still more vacancies being advertised than before the pandemic, workers are much less likely to quit their jobs. Consumers report jobs are harder to find, and small employers have slashed hiring plans.

Friday’s payrolls figures showed the second-lowest monthly number of new jobs since October, and the rise in hourly earnings was small.

Credit: More consumers and companies are struggling to cope with the interest burden on their debts. More than 3% of borrowers failed to pay their credit-card bills on time in the fourth quarter of last year, the highest delinquency rate since 2011, and double the low reached three years ago. Young and poor borrowers who took out loans to buy a car or truck are also getting into trouble more often than before the pandemic.

Something similar is going on with companies: Those closest to the edge are at much greater risk of tipping into bankruptcy than normal—even as profit margins for the biggest companies remain high.